Sermon 27 December 2020 | Liz Caughey

My title for this sermon is ‘Reading between the lines’. Anyone who’s spent time with me will know that language has always played a big part in my life. Not just speaking languages, but enjoying their grammatical complexity. I could tell you many stories about apostrophes and semi-colons, not to mention the Oxford comma. Although I have no doubt that this is an irritating trait for my fellow Vestry members to endure, it has an upside for me.

It’s through words in whatever form that I predominantly receive the Word of God. So for me, Scripture is a treasure trove – the Old Testament, the Gospels of the New Testament – and its other books…. The Psalms, the Proverbs, the rich poetic language of Isaiah, the humanness of the letters of Paul and Timothy – I have so many favourites. The Scriptures are the most beautiful footprint of our faith – inspired stories that are part-history and part-myth – that convey everything from deprivation, oppression, protest and anguish to glory, holiness, redemption and resurrection. And over the centuries, these oral histories were committed to writing in manuscript form. They provide a resource of life-giving, inspirational and aspirational material for anyone who has a mind to read them, in any place and any time.

I was really surprised when I realised where this sermon was taking me during this past week. The thing with sermons is that they tend to bring you back to the same theme no matter how hard you try to move away. I was reading the Gospel passage, when a detail caught my eye. Simeon is the first to honour Jesus at the Temple, and Luke gives him 3 paragraphs to do that. Anna is the second. She has one paragraph but over one-third of it relates to her father, her patriarchal tribe and her deceased husband. So she herself actually gets very little story. And so, I began thinking about the women, and in particular Jesus’ mother Mary and how she is portrayed – such a key person in the Christian story, the earthly genesis of the incarnation of Christ.

She is certainly not given many lines to speak, but what a part she played! And what an influence she has had through her actions rather than her words….. as we are encouraged to do. Mary of Nazareth, mother of Jesus. In the Catholic tradition, she is venerated. I think we Anglicans can benefit from borrowing from them from time to time – especially in the Christmas season – to acknowledge Mary and honour her as the mother of God incarnate. Mary, whose perspective isn’t often conveyed.

For example, I am aware that today, historically, is just two days after Jesus’ birth. Many of the women in our congregation will know what that’s like in a very real sense. The exhaustion, the physical toll, the disbelief, the sense of wonder, the flashbacks to the birth, the emotional ups and downs – and perhaps some fear of responsibility or future. None of this is even alluded to in the Bible but that doesn’t mean it isn’t hugely important. As women, we can imagine this part of Mary’s story.

It’s important to look behind the given narratives to see the ‘other’ – for example, the women, and other marginalised groups. By drawing out their experience or perspective, we can see a fuller picture than what is being presented.

For over 2000 years, the Bible has told of Mary’s steadfast faithfulness and obedience to God. But we can also interpret from the text that she had other strengths that haven’t been highighted. Such as the way she conducted herself in the face of her extraordinary situation. She demonstrated a depth of autonomy and courage and calm that somehow seem unexpected from a woman living in an era when women had no power – nor any social standing unless they had a father, brother or husband as protector, and to provide a legitimising link to society.

The Angel Gabriel doesn’t treat Mary like the property of a male, but as a respected individual. He approaches her with deep reverence. No wonder Mary was perplexed. …. And yet it seems she had a deep intuitive understanding of what was being asked of her and of what was about to unfold – that she would put God’s will before her own life.

Her agreement was given without consultation with others, telling us that this is her decision alone. She doesn’t need the permission of the priests – or her parents – or Joseph – to become pregnant. Her decision was based not on the social stigma of being with child before she is married, nor the risk that Joseph would leave her, but simply on whether or not she would do God’s will.

And by accepting God’s will, she became a beacon for all women to take action for God’s will – God’s justice – which is so often absent in this world. Perhaps Mary is sought out by God precisely because of her courage to be independent and decisive in the face of societal expectations and constraints.

It’s always important to consider who the author of a history is. Historically, it hasn’t been women or other marginalised or minority groups. Very few women were taught to write in the first century, so in the Scriptures women’s participation was recorded from a male perspective, if at all. Although Mary is key to the Christ story, her experience mostly isn’t represented other than as a voiceless support to the actions of men. The narrative is heavily from one perspective, and therefore incomplete.

Subsequent to these written histories, theological commentary has traditionally been written by men, and sermons were preached by men for a very long time before women were allowed. In fact, over the centuries God has even been attributed a male persona – the default seems to be to refer to God as ‘He’. Any suggestion of an ancient feminine Divine was overtaken by the masculine.

It seems illogical to me that God would be male only. As an all-powerful entity, surely God must be all genders – in the broadest sense – and no gender. In fact, to try to describe God using human language is to contain ‘him/her/them’, within the human dimension. It can only restrict God. For me, the closest description of God is found in a symphony, a song, a sunset, an electrical thunderstorm, or the miracle of a newborn baby – which is, after all, what Maryof Nazareth brought into the world – at such risk to herself.

The themes of the Bible are universal and timeless, and that is the beauty of it. Although written in the first century, the message mostly transposes and relates to our time very clearly. What I find interesting is that I’ve never felt excluded by the male lens of the Scriptures. But I’m aware that it’s important to look at what’s going on behind the narrative. And so too, we must look behind the dominant narratives of our lives, to recognise and uplift the unheard perspectives and stories of those whose voices are not valued and listened to. Each time we do this, we make a difference in someone’s life, and that is one more way we can be Christ in the world.

What remains is that we all, women and men, are loved by God. God has found favour in each of us because of our uniqueness. We all have gifts from God – perhaps some we aren’t yet aware of – regardless of our age, gender, complexity and frailties. Let’s be inspired to develop those gifts, and to use them for the glory of God and the good of those around us.

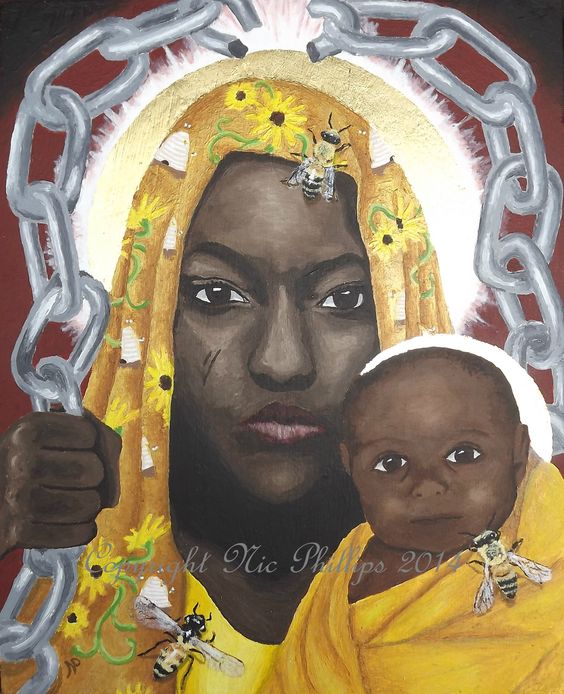

And this Christmas season, let us all remember and honour Mary, and give thanks to God for this courageous young woman who brought Christ to us. And I wanted today to specifically remind the women of the church that we come from strong stock. We are all of the tribe of Mary. The tribe of Mary – a strong-minded young woman who gave birth to Christ and changed the course of history. Let us make sure our stories and our voices are known. Let’s bring forward our gifts and strengths, our faithfulness and obedience, to benefit others, in the name of Mary’s Son, Jesus Christ Our Lord. Amen.

[Following the sermon, Catherine Hamilton and Loimata Lilo, introduced as ‘two wonderful representatives of the tribe of Mary’, performed a Christmas version of Hallelujah, by Leonard Cohen]